A new brain-machine interface (BMI) uses light to "speak" to the brain, mouse experiments show.

The minimally invasive wireless device, which is placed under the scalp, receives inputs in the form of light patterns, which are then conveyed to genetically modified neurons in brain tissue.

In the new study, these neurons activated as if they were responding to sensory information from the mice's eyes. The mice learned to match these different patterns of brain activity to perform specific tasks — namely, to uncover the locations of tasty snacks in a series of lab experiments.

The device marks a step toward a new generation of BMIs that will be capable of receiving artificial inputs — in this case, LED light — independent of typical sensory channels the brain relies on, such as the eyes. This would help scientists build devices that interface with the brain, without requiring trailing wires or bulky external parts.

"The technology is a very powerful tool for doing fundamental research," and it could address human health challenges in the longer term, said John Rogers, a bioelectronics researcher at Northwestern University and senior author of the study, which was published Dec. 8 in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Bypassing the sensory system

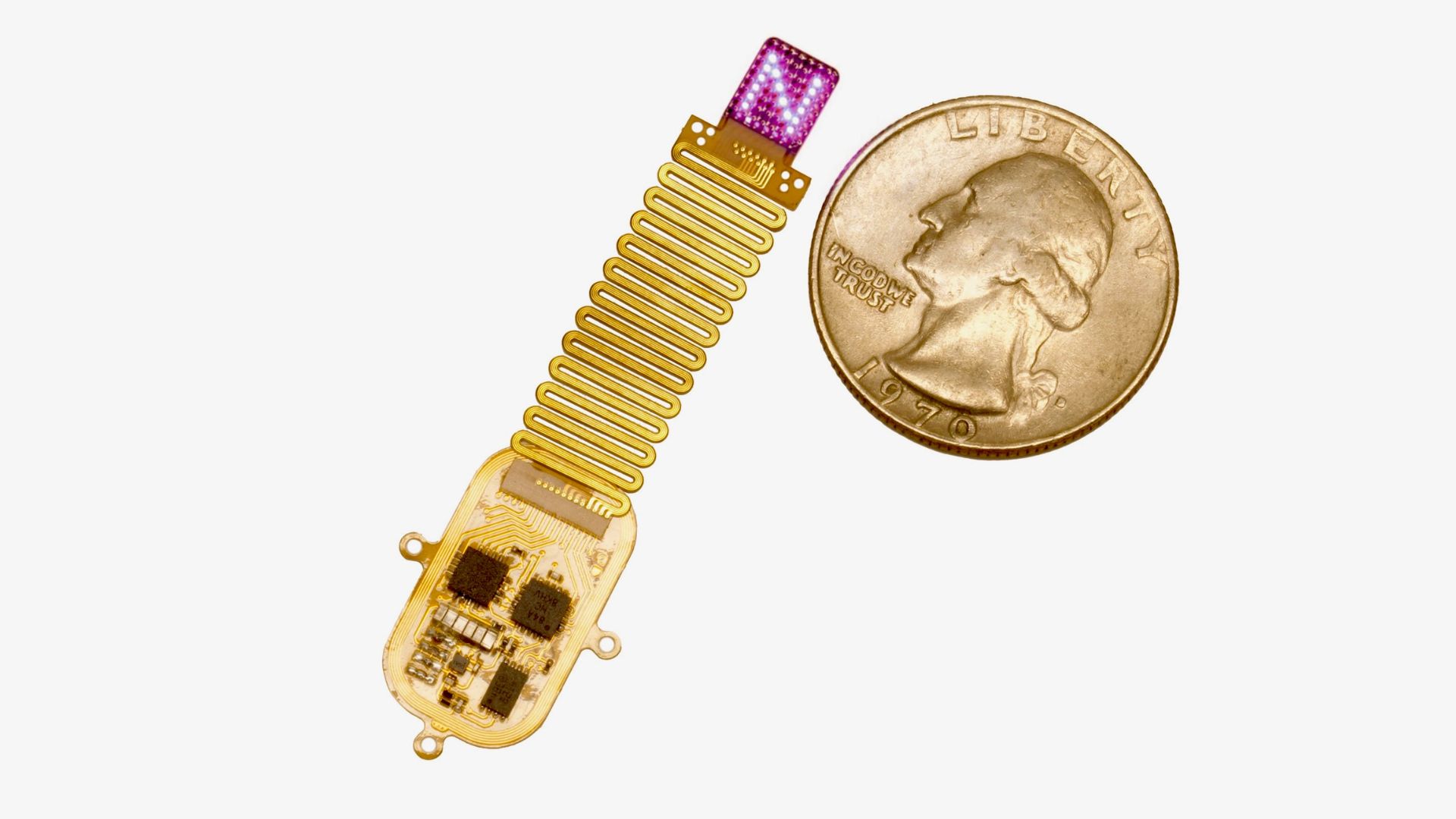

The device, which is smaller than a human index finger, is soft and flexible, so it conforms to the curvature of the skull. It includes 64 tiny LEDs, an electronic circuit that powers the lights, and a receiver antenna. Additionally, an external antenna controls the LEDs using near-field-communications (NFC) — electromagnetic fields for short-range communications as is done for contactless card payments.

The compact device is designed to be placed under the skin, rather than being implanted directly into the brain. "It projects light directly onto the brain [through the skull], and the response of the brain to that light is generated by a genetic modification in the neurons," Rogers told Live Science.

Brain cells don't normally respond to light that is shone on them, so gene editing is required to make that happen.

"The genetic modification creates light-sensitive ion channels," Rogers explained. When activated by light, these channels allow charged particles to flow into brain cells, tripping a signal that then gets sent to other cells. "Through that mechanism, we create light sensitivity directly in the brain tissue itself," he said. The genetic modification of the brain cells was done using a viral vector, a harmless virus made to deliver the desired genetic tweak into specific cells in different regions of the brain.

The use of light to control the activity of genetically modified cells is called optogenetics, and it's a relatively new science. In past work, the researchers used a similar approach to activate just one group of brain cells, but the new device enabled them to toggle the activity of many neurons across the brain.

"[The genetic modification] is not just stimulating the part of the brain that's naturally responsible for visual perception, but across the entire surface of the cortex," Rogers said. Thus, sending different patterns of illumination creates a corresponding distribution of neural activity. "It's like we can project a series of images — almost like play a movie — directly into the brain by controlling [the] sequence of patterns."

The researchers tested the implant in the mice by wirelessly instructing it to produce various patterned bursts of light. The mice were trained to respond to each pattern with a specific behavior, indicating that they could distinguish between the patterns transmitted. With each type of signal, they had to go to a specific cavity in a wall, and for choosing correctly, they'd get sugar water as a reward.

Bin He, a neuroengineering researcher at Carnegie Mellon University who wasn't involved in the study, called it a novel technique for using light to tune circuits across the brain. "It may have various applications in neuroscience research using animal models … and beyond," he said.

For instance, the researchers see potential for this device in future prosthetics. Applications could include adding sensations, like touch or pressure, to prosthetic limbs, or sending visual or auditory signals to vision or hearing prostheses.

"Optogenetic techniques are just beginning to be used with humans," Rogers said. "There are tremendous advantages [to using light] because you don't need to disrupt the brain tissues. You can use different wavelengths of light to control different regions of the brain."

Rogers said that from a technology standpoint, the platform could scale to cover much larger areas of the brain and contain more micro-LEDs. However, they would have to rethink the power-supply requirements to support a larger device. It should technically work in humans as it does in mice, but further research will be needed before any tests are attempted in humans.

"The biggest hurdle is around the regulatory approval for the genetic modification," he said.

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·