It is often difficult for people in India to remember life before Aadhaar. The digital biometric ID, allegedly available for every Indian citizen, was only introduced 15 years ago but its presence in daily life is ubiquitous.

Indians now need an Aadhaar number to buy a house, get a job, open a bank account, pay their tax, receive benefits, buy a car, get a sim card, book priority train tickets and admit children into school. Babies can be given Aadhaar numbers almost immediately after they are born. While it is not mandatory, not having Aadhaar de facto means the state does not recognise you exist, digital rights activists say.

For Umesh Patel, 47, a textile business owner in the city of Ahmedabad, Aadhaar has brought nothing but relief. He recalls the old days of bringing reams of paper to every official office, just to prove his ID – and confusion often still reigned. Now he simply flashes his Aadhaar and “everything is streamlined”, he said, describing it as a “marker of how our country is using technology for the benefit of its citizens”.

“It’s a robust system that has made life much easier,” said Patel. “It is also good for the security of our country since it reduces the chances of anyone making fake documents.

“Aadhaar is now part of the Indian identity.”

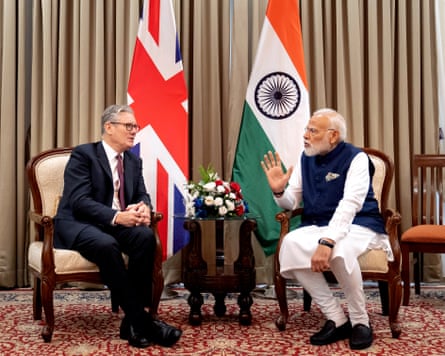

The scheme has been deemed such a success that it was among those studied by the UK government as it looks to introduce mandatory ID cards for all citizens. Yet digital rights groups, activists and humanitarian groups paint a less rosy picture of Aadhaar and its implications for Indian society.

For some of the poorest and least educated in India – whose lack of literacy, education or documents have left them unable to get an Aadhaar – the scheme has been highly exclusionary and therefore punitive, depriving some of those who need it most from being able to receive welfare or work. And as there is a growing push to have Aadhaar linked to voting rights and proof of citizenship, there are fears it will become a tool to further disenfranchise and demonise the poor.

Apar Gupta, the founder and director of the Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation, said that, for many in India, Aadhaar had turned into a form of “digital coercion, in which each and every time they need to avail a government service, enter a public space or just conduct their lives, there is a constant demand for Aadhaar-based authentication”.

Gupta said that since its introduction Aadhaar had “metastasised” and become the basis of an ever-expanding bureaucratic minefield of unique IDs required in order for people to conduct business. “Your very basis to live is checked at each and every step,” he said.

Critics allege that India’s most recent data protection and privacy law, which remains in draft form, is not fit for purpose in protecting the privacy and possible misuse of the highly valuable and sensitive Aadhaar database, which includes biometrics such as photos, face scans, iris scans and fingerprints of more than 1 billion Indians.

Over the years, the Indian media have uncovered numerous breaches of Aadhaar data, including an incident in 2018 when it was discovered that the details of 1.1 billion Indians on the Aadhaar database were being sold online for as little as 500 rupees (£5).

“Under this law, which has still yet to be notified, there is no way to know if there has been a reported data breach and no oversight into how Aadhaar data may be bundled with other databases, which could enrich wider tracking and surveillance of citizens,” said Gupta. “There’s a complete lack of transparency.”

While Aadhaar was introduced before the prime minister, Narendra Modi, came to power in 2014, his ruling Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) has embraced and expanded the unique digital ID scheme with gusto. As India hosted the G20 summit in 2023, Modi cited Aadhaar as one of the key successes of a “digital India” that had become an “incubator of innovation”. He has claimed that it has saved India more than $22bn in wiping out corruption in welfare schemes.

The government has also pointed to Aadhaar’s vast adoption as a measure of its success and universality. More than 1.42bn Aadhaar numbers have been generated as of last month – almost the exact size of the population of India itself – making it the world’s largest digital identity scheme by a long mile. Before the scheme, more than 400 million Indians lacked any form of official ID and did not have access to a bank account.

Yet, according to Chakradhar Buddha, a senior researcher at LibTech India, an organisation that has been assisting those left behind by India’s digital push, the reality on the ground – particularly in rural and tribal communities – was very different to that being painted by the government in Delhi.

after newsletter promotion

“We have seen those in tribal, hilly or remote areas being unable to get an Aadhaar – and it’s happening on a large scale that goes unacknowledged,” said Buddha.

“Partly it’s because they might not have the right documents or their different documents don’t catch completely; partly it’s because the technology keeps changing and creating additional hurdles that punish the most vulnerable. Ultimately, it’s a system that undermines access to essential social security and welfare for those that need it most.”

The government’s insistence that Aadhaar is a watertight identity verification was questioned by Buddha, who said he had seen many examples of officials recording inaccurate names or details, creating greater problems for communities. In one village, where a tribal community did not have birth certificates, they were all given 1 January as their birthday. Tribal names are also regularly spelt wrong on Aadhaar cards as officials are unfamiliar with them.

Buddha warned that using Aadhaar as a universal basis for voting rights would lead to a “mass expulsion of the poorest from the electoral register”, citing a recent example where millions of India’s poorest workers were wrongly deleted from a government system, depriving them of a livelihood, after an Aadhaar verification system was enforced.

“These people are already deprived of social equality; now they want to use Aadhaar to strip away their right to political equality and universal franchise,” said Buddha.

Among those who recently came up against the perils of being without an Aadhaar card was Aalam Sheikh, 34, an illiterate labourer, whose bag containing important ID documents and Aadhaar card was stolen on a train.

What followed was a Kafkaesque nightmare. Not knowing his Aadhaar number, which he was given a decade ago, he had no way to get a new card. Without it, he was stopped from working his construction job, depriving his family of a vital income, and his son was later forced to withdraw from school.

Months later, Sheikh has still been unable to resolve the problem and get a new card, even after travelling thousands of miles back to his village. Meanwhile, he lives in fear of being declared an illegal citizen without it.

“This Aadhaar has become a nightmare for us. Why can’t the government maintain a proper system?” said Sheikh. “Everything in this country works against the poor, and so does this Aadhaar card.”

Aakash Hassan contributed reporting

.png)

3 hours ago

21

3 hours ago

21

English (US) ·

English (US) ·