Researchers have uncovered an intriguing set of never-before-seen features in the skull of Archaeopteryx, an iconic dinosaur that is considered a key transitional fossil in the evolution of birds, a new study reports.

The features — which are absent in nonflying dinosaurs but are widespread in living birds — may have enabled Archaeopteryx to acquire, manipulate and process food more efficiently, the research team proposed in the study, which was published Feb. 2 in the journal The Innovation.

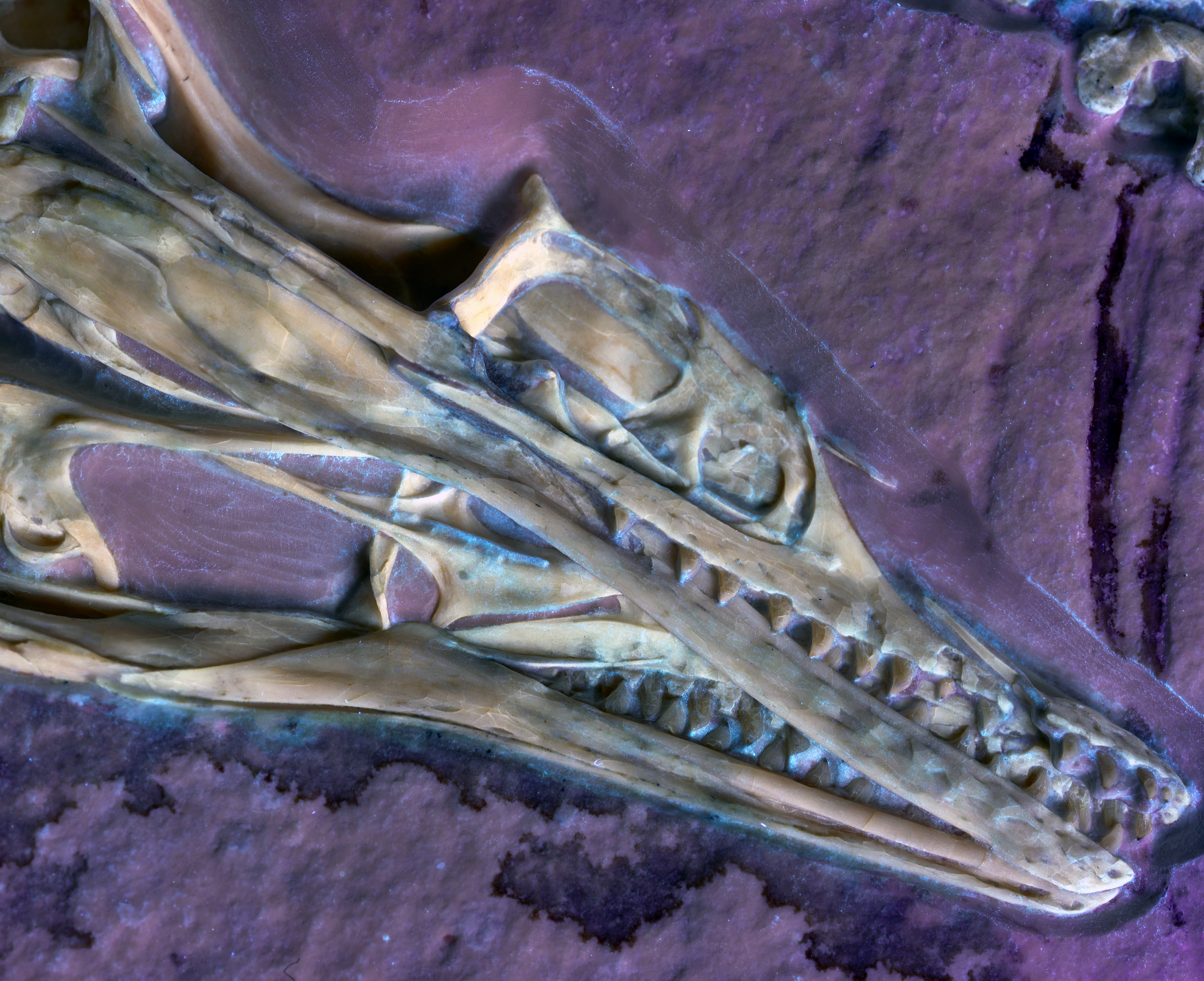

The newly discovered features include a tiny bone that indicates Archaeopteryx had a highly mobile tongue. The researchers also identified "weird" soft tissue traces interpreted as oral papillae — small, tooth-like projections on the roof of the mouth, Jingmai O'Connor, an associate curator of fossil reptiles at the Field Museum in Chicago and lead author of the study, told Live Science in an email. Finally, the team found "unusual" openings near the tip of Archaeopteryx's jaw that suggest a nerve-rich structure and may represent an early analogue of what is known as a bill-tip organ in modern birds.

The identification of these features in Archaeopteryx marks their earliest known appearance in the fossil record, according to the study, suggesting these characteristics evolved during or close to the emergence of avian dinosaurs — known as birds — which is thought to have occurred during the Late Jurassic period (roughly 161.5 million to 143 million years ago).

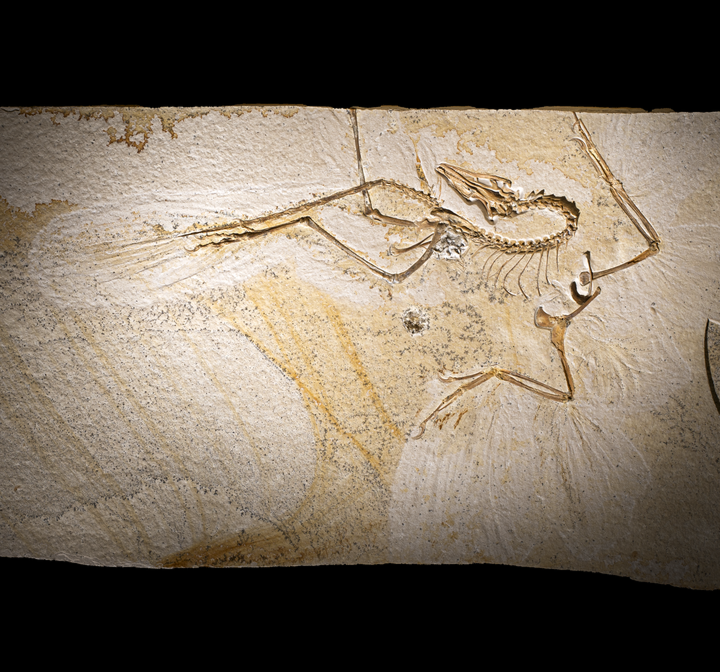

Modern birds are the only dinosaur lineage that survived the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. Archaeopteryx, which lived around 150 million years ago in what is now Germany, is among the oldest — if not the earliest — known dinosaur that can also be considered a bird under a broad definition, although it was probably not the first bird to evolve, O'Connor said.

Furthermore, Archaeopteryx is unlikely to have been a direct ancestor of modern birds, research suggests. According to O'Connor, Archaeopteryx represents the earliest known dinosaur with good evidence for active, feather-driven flight, although this was likely limited to brief, powered bursts.

The newly revealed features came to light during the preparation and examination of an Archaeopteryx specimen at the Field Museum that was first described scientifically in 2025.

Oral papillae help birds grip prey and guide food down their throats. This is the first time such features have been documented in the fossil record, the study noted. The flexible tongue, meanwhile, likely would have helped Archaeopteryx reach for food and manipulate it. Bill-tip organs in birds provide "added sensory information" that helps with a variety of oral tasks, such as rummaging around for food, O'Connor said.

The latest findings about Archaeopteryx, which indicate a change in dinosaur feeding abilities occurring around the origin of birds, raise the "interesting possibility" that the evolution of the novel features was driven by the increased energy demands associated with the emergence of powered, feather-driven flight, the authors propose.

Christian Foth, a paleontologist with the Museum für Naturkunde (Natural History Museum) in Berlin who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the paper has some "interesting findings" that should be explored further in other Archaeopteryx, early-bird and bird-like-dinosaur specimens. But he said he was not convinced by the authors' proposal for a new bill-tip organ analogue in the snout, and urged caution over the suggestion that the features evolved as adaptations to Archaeopteryx's flying behavior.

"Active flight requires energy, correct. But how many calories the animal in the end could use for flight depends more on the diet source itself and the digestion system, which we do not have any info on," Foth said. These adaptations may "ensure that a caught dragonfly did not fall out of the mouth," he added, "but not how well the diet was processed."

O'Connor, Jingmai K., Clark, A. D., Kuo, P., Wang, M., Shinya, A., Beek, V., & Chang, H. (2026). Avian features of Archaeopteryx feeding apparatus reflect elevated demands of flight. The Innovation, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2025.101086

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·