QUICK FACTS

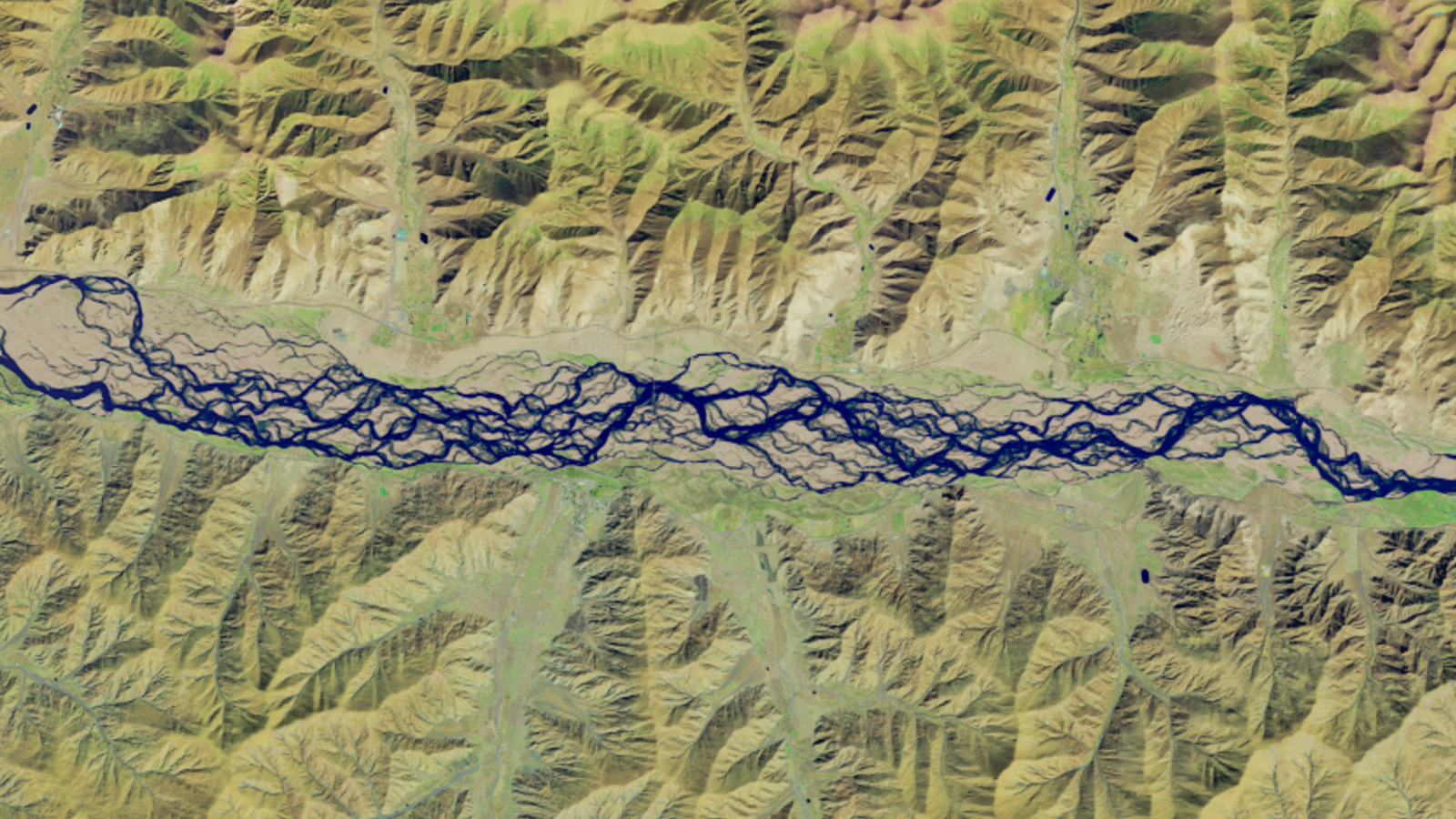

Where is it? Yarlung Zangbo River, Tibet Autonomous Region of China [29.2814054, 91.3256581]

What's in the photo? The braided branches of a river winding through the Tibetan Plateau

Which satellite took the photo? Landsat 9

When was it taken? Feb. 8, 2025

This striking satellite photo shows a particularly convoluted section of a record-breaking "braided river" in China, which drastically changes shape every year and could become more unstable over the coming decades due to climate change.

The photographed section of the river is located in Zhanang County, just before it passes through the world's deepest land-based canyon and its namesake, the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, which is more than 6,000 meters (20,000 feet) deep — or three times deeper than Arizona's Grand Canyon.

Yarlung Zangbo is a classic example of a braided river — a waterway with "multi-threaded channels that branch and merge to create the characteristic braided pattern," with mid-channel sandbars that are "formed, consumed, and re-formed continuously," according to the National Park Service.

This section is where the most braiding occurs anywhere along the river, with up to 20 channels across at certain points in the image.

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

Yarlang Zangbo's extreme braiding is caused by heavy sediment deposits from the steep slopes of the adjacent Himalayas, which are washed into the river and help carve new channels into the ground, Zoltán Sylvester, a geologist at the University of Texas at Austin, told the Earth Observatory. The river changes shape so often that no vegetation can fully grow on the sandbars that sporadically appear between the river's braids, he added.

You can see how quickly the river changes shape for yourself in a 37-year timelapse animation, which shows annual satellite images of this spot taken between 1988 to 2025 by Landsat 5, Landsat 8 and Landsat 9 (see below).

Eagle-eyed viewers may also be able to spot a narrow bridge, which was constructed over the shapeshifting waterway in 2014. (It's visible as a thin line near the far right-hand side of the animation).

The river starts at the Angsi Glacier, emerging from a stream of meltwater that flows from the ice mass. However, this was only officially confirmed in 2011, according to Chinese state media. Before this, there was confusion among scientists about whether the river actually originated from a meltwater stream coming from the nearby Chemayungdung Glacier.

Like many other Himalayan ice masses, the Angsi Glacier has lost a significant amount of water in recent decades due to human-caused climate change. The resulting meltwater has caused more sediment to be deposited into the river, which can increase erosion and make it more likely for its banks to collapse. According to a 2024 study that analyzed satellite photos of the 13 major rivers in the Tibetan Plateau, this poses a risk to local ecosystems, infrastructure and landscape stability.

When the river eventually reaches India, it becomes part of the Brahmaputra River and continues for another 1,800 miles (2,900 km) until it reaches the Ganges River Delta, where it drains into the Indian Ocean, according to the Earth Observatory.

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·